Microdiscectomy versus Open Discectomy |

|

The Procedure | Proper Candidate | Surgery Timing | Research | Open Discectomy | Microdiscectomy | History of Herniation & Discectomy | Surgery Position | Picking vs. Sequestrectomy | Endoscopic Discectomy

When a lumbar disc herniation occurs, it usually happens in the posterolateral region of the disc, which in turn irritates the traversing nerve root and causes not only back pain, but also a terrible radiating, burning pain down the lower extremity—usually into the foot (i.e., sciatica).

What's the fix? For disc herniations that are refractory to conservative care, a surgical technique called Open or Mirco-discectomy are the gold standard treatments.

How does it work? In the grand scheme of things, the surgeon's mission is to surgically remove (excise) the herniated portion of the disc – the part that is pinching/irritating/inflaming the nerve root and making the patient's life quite miserable. By removing the disc herniation, the pressure is in turn removed from the nerve root, which usually rapidly diminishes the leg pain greater than back pain.

|

|

Figure #1: Here we have the clinical picture (axial view {from below}) of a L4 lumbar disc that has ruptured through the annulus fibrosus (annulus) and compressed the left L4 exiting nerve root, as well as the L5 traversing nerve root. Figure #2: The surgeon has cut through the skin and dissected the muscle and fascia away from the spinous process (SP). Next a retractor was placed so that it pulls back the loose muscle and fascia laterally in order to create a work space. |

|

|

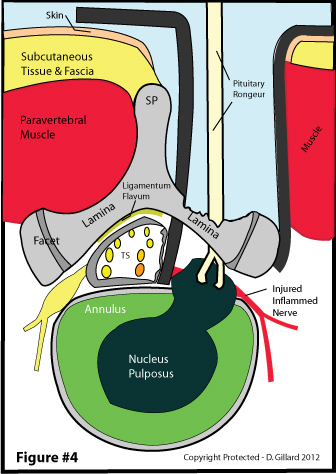

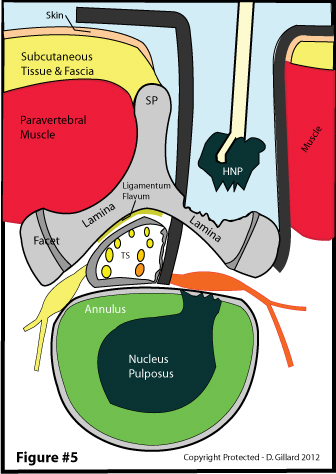

Figure #3: In order to access the anterior epidural space, which is where the herniation is located, the work space must be continued down. So the bony lamina is partially removed (laminotomy), which reveals the final guardian of the epidural space: the ligamentum flavum. It too is removed (pink star). Next another retractor is used to push the thecal sac and nerve root medially (out of the way). finally, the HNP is revealed. Figure #4: Using a pituitary rongeur, the surgeon grabs onto the herniation and starts tearing it out chunk by chunk (figure #5). |

|

Figure #5: After the last of the visible fragment of herniation is removed, a thorough and diligent inspection of the epidural space is made in order to insure that no sequestered fragments of nucleus pulposus are hiding anywhere. Then the wound is closed and the surgery is complete. A more in-depth description of open discectomy technique can be read here.

|

A PROPER CANDIDATE:

Does discectomy really work? The short answer is typically yes, especially for the sciatica, but only IF YOU ARE A PROPER CANDIDATE WHO HAS NOT WAITED TOO LONG!

So who is a proper candidate? A proper candidate can be defined as the patient who has (1) imaging evidence (MRI, CT myelography, and/or CT discography) of a herniation that matches the neurological deficit on exam; (2) nerve root tension signs (i.e., a positive straight leg raise or reverse straight leg raise test); and (3) subjective complaints that match the former and latter criteria.

Who are mandatory candidates? the short answer is this: (1) cauda equina syndrome; (2) severe progressive neurological findings; and (3) severe intractable pain. let's talk about them:

Sometime the disc herniation is so large and so compressive that the nerves that control the bowel and bladder become dysfunctional to the point voluntary control is lost-- this is called cauda equina syndrome. More specifically, the patient will lose control and start accidentally urinating and/or defecating in their under-garments. This horrible syndrome is often preceded by a numbness, tingling, burning in a saddle-like distribution over the anus and genitalia (i.e., the perineal area) (THIS IS A MEDICAL EMERGENCY and is something that must be addressed immediately or risk suffering permanent loss of control to the structures.

Other opinions:

The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons and Alf Nachemson – who was the number one spine researcher in the world (18) -- recommends the following conditions be met before decompressive surgery is offered:

#1 |

Functional incapacitating pain in the leg, extending below the knee with a nerve root distribution. |

|---|---|

#2 |

Nerve root tension signs (positive straight leg raising test) with or without neurologic abnormalities, fitting the radiculopathy. |

#3 |

Failure of clinical improvement after 4-8 weeks of conservative treatment, |

#4 |

Confirming imaging study: abnormal myelogram, computed tomogram (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) correlated to the physical signs and distribution of the pain. |

SURGERY TIMING: When to Say, "Enough Is Enough" and Succumb To Surgery.

The Short answer is that you should only fool around with true disc herniation-induced sciatica for three or four months--if it ain't better by then, and you meet the above criteria, then you should seriously consider having open/microdiscectomy surgery.

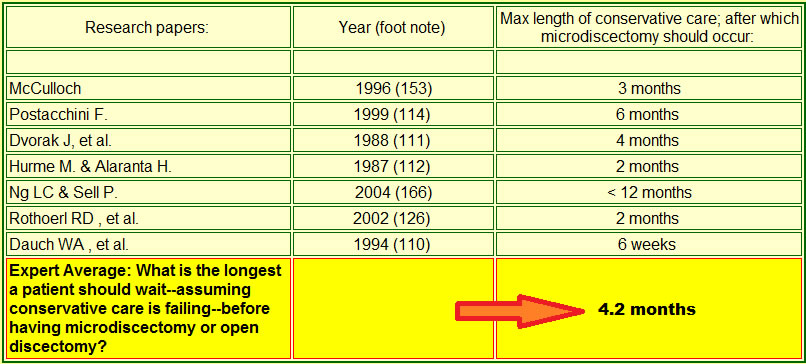

The following is a chart I made regarding the outcomes of investigations into this important topic. As you can see, based on the medical literature, you shouldn't wait more than four months--one year maximum, for after that time, the chances of affording a successful discectomy are drastically diminished (although that certainly doesn't mean that with the passage of time you won't get better--in fact, you will probably achieve about the same outcome as if you were to have surgery; although, it may take years (so surgery is a quicker fix) [13].

|

As you can plainly see, the medical research demonstrates that a patient should not wait longer than 4.2 months before succumbing to micro/open discectomy. However, if the patient is improving with conservative care and does not meet all the criteria listed above, then perhaps continued conservative care is in order. Remember, always discuss this evidence thoroughly with your doctor before making a decision, for having surgery is a big deal when it comes to the spine--things can go wrong. |

Also keep in mind that researchers consider a "surgical success" to be defined as a 50% improvement in patient VAS scores--so if your VAS drops from an 8 to a 4, you are considered to have had a successful surgery. It's certainly the minority of patients who get 100% better following surgery.

Let's prove it sometime works:

THE RESEARCH: What Are My Chances for Success Following Discectomies?

What does the research say about the chances of having a successful open/microdiscectomy? While there are hundreds if not thousands of investigations describing the efficacy and outcomes of discectomy, arguably the best research study on the subject to date is the Maine Study [1]:

In 2005, Atlas et al. published the results of their 10 year outcome study, which followed 507 patients in whom suffered disc herniation-induced back pain and sciatica. At the 10 year time point, 84% of these patients were available for the follow-up, which makes this a high-quality investigation. At the beginning of the study, approximately 1/2 of the patients were allocated into conservative care, while the remaining 1/2 were allocated to discectomy surgery (this group actually had more severe symptomatology). At the 10 year time point, 56% of the surgical patients reported that their low back and leg pain were much better or completely gone. However, only 40% of the nonsurgical patients reported such improvement (P = 0.006). Patient satisfaction was also statistically higher in the surgery group: 71% of the surgery patients were satisfied with their outcome, while only 56% of the nonsurgical patients were satisfied (P = 0.002). However, despite the favorable subjective performance of discectomy, both groups were statistically equal with regard to the ability to work and disability status at 10 years.

[Is it my "research corner," for a whole bunch more studies].

So, let's run out and get a discectomy. Ah, things aren't quite so simple because there are many "flavors" of discectomy: there are the open discectomy, microdiscectomy, laser discectomy, endoscopic discectomy, percutaneous discectomy, Nucleoplasty, and chemonucleolysis (a form of discectomy). So which one is the "gold standard" –i.e., the one that is most accepted by the majority of scientists and physicians?

What is the short answer? The so-called "gold standard" for combating symptomatic disc herniation-induced sciatica and back pain is either the open discectomy or microdiscectomy.

THE MEAT AND POTATOES: LET'S GET TECHNICAL.

Will the Real Gold Standard Please Stand UP: Open Discectomy Versus Microdiscectomy

OPEN DISCECTOMY: (aka: standard discectomy):

As all astute physicians know, 1934 was a good year. This is because the timeless mystery of sciatica (which has plagued mankind long before the days of Hippocrates (300 B.C.)) was finally solved and the open discectomy was born.

The procedure was very crude at first. More specifically, they used to do a complete laminectomy (completely remove the lamina on both sides); flavectomy (completely remove the ligamentum flavum on both sides) and finish by cutting right through the CSF-containing thecal sac (transdural approach) in order to access the herniation (transdural approach)--indeed a very scary surgery. The amount of scar tissue that must have been generated is unthinkable!

Subsequent modifications, however, created the very successful procedure for the treatment disc herniation-induced sciatica [1, 13] that we have today. These included the usage of a minimal laminotomy in place of laminectomy [73] (they no longer took the whole lamina out, which minimized scar tissue formation and helped maintain stability of the motion segment) and minimal flavectomy (they saved as much of ligamentum flavum as possible, which again helps with stability and minimizes scar tissue formation).

More recent modifications to the open procedure include the use of magnification loupes and headlights [3], which assist the surgeon by magnifying the dissection and herniation extraction process. Some authors have argued that by using such equipment, the procedure is more properly termed a microdiscectomy.

MICRODISCECTOMY (aka microsurgical discectomy):

Grafton Love, a surgeon at the Mayo Clinic, put his twist on the open discectomy technique in 1939, using what he called a "key hole" laminotomy to access the epidural space--microdiscectomy was born [73].

In 1977, Yasargil [24] and Caspar [25] independently described the addition of a powerful operating microscope to the open discectomy procedure that resulted in a much more minimally invasive procedure. That is, the microscope greatly increased the physician's vision, which in turn resulted in smaller and cleaner dissections down to the disc herniation. Arguably, this precision results in less soft tissue damage and less postsurgical scarring (epidural fibrosis and perineural fibrosis), which in turn yields better patient outcomes when compared to traditional open discectomy. And that superiority is just what the first outcome study on microdiscectomy demonstrated [5]. Current studies, however, are not so persuasive (see below).

So the touted advantages of microdiscectomy by some proponents include a cosmetic advantage (smaller skin incision); shorter hospital stay; and less blood loss during surgery. The big disadvantage, which has been extensively reported upon,is that the smaller operating field may make some fragments of disc herniations more difficult to retrieve or even completely missed [20, 21].

If the space between the lamina of the vertebra above and the lamina below is wide enough (like at L5/S1, which by the way is called the interlaminar space), then usually only the ligamentum flavum is all that needs to be removed; however, usually some degree of laminotomy (a piece of the lamina is removed) is needed, as is a limited medial facetectomy. The tools needed to perform this are typically rongeurs and Kerrison punches.

As a side note it should be noted that epidural fibrosis/perineural fibrosis (scar tissue) is the bane of every surgeon and patient, for it is the leading cause of failed back surgical syndrome (a surgery that not only didn't work, it made the patient worse) [6, 7].

So Which One Is the True "Gold Standard": Open Discectomy or Microdiscectomy?

Notwithstanding retrospective and prospective observational studies on both sides of the fence, it was the three randomized controlled trials [4, 8, 9] on the subject, which demonstrated no superiority between the two techniques, that settled the dispute and led some of the leading researchers in the world to opine that open discectomy and microdiscectomy are both the gold standard treatment for symptomatic disc herniation [17, 18].

History of Disc Herniations-Induced Sciatica and Back Pain:

This page would be incomplete without a historical discussion leading up to that landmark discovery that a herniated intervertebral disc could result in lower back pain as well as terrible radiating lower extremity pain (sciatica).

No doubt humans have toiled with back pain and sciatica since they evolved to an upright posture, which in turn pressurized the intervertebral disks. The first written reports of back pain and sciatica surfaced in the ancient medical text The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, which was ostensibly written around 1550 BC [10].

The famed German pathologist, Hubert von Luschka, was the first to thoroughly describe the different classes of disc herniation back in the 19th-century. Notwithstanding his thorough descriptions (which were gleaned from cadaver dissection), not only did he fail to clinically associate these herniations with back pain and leg pain, he also erroneously described these disc protrusions as cartilaginous tumors of the disc.

In December 1908, German surgeon Fedor Krause performed the first successful discectomies/laminectomy on a patient who suffered from severe sciatica that had progressed into cauda equina syndrome [90]. However, despite the resolution of sciatica and urinary incontinence, he still didn't put two-and-two together and opined the patient's incontinence was secondary to a discal enchondroma (cartilage tumor)—in reality, the large mass he removed from the disc was a large disc herniation.

Professor Walter E. Dandy, a neurosurgeon at John Hopkins, was almost there when he published a revolutionary hypothesis that these masses in the posterolateral region of some intervertebral discs were not tumors but in fact were made of discal tissue [26]. Furthermore, he postulated that these masses could in fact produce patient sciatica by compressing the adjacent nerve roots. He even proclaimed that by their removal, the patient's pain could be cured. Unfortunately, little attention was paid to his publication because he continued to call these disc protrusions tumors-- that was his only mistake. Dandy, however, is often credited with performing the first surgical treatment for a disc herniation that resulted in cauda equina syndrome in two patients [30].

|

The Famous Mixter & Barr: In 1934, American neurosurgeon William J. Mixter and orthopedic spine surgeon Joseph S. Barr, rocked the medical world by proclaiming that these supposed enchondroma of the disc were nothing more than protrusions of disc material from within the same disc. These Massachusetts general doctors also explained how compression of the nerve roots could create the symptom of sciatica as well as back pain. "We conclude from this study: that a herniation of the nucleus pulposus into the spinal canal, or as we prefer to call it, rupture of the intervertebral disc, is a not uncommon cause of symptoms. That the lesion frequently has been mistaken for cartilaginous neoplasm arising from the intervertebral disc…. That the treatment of this disease is surgical and that the results obtained are very satisfactory if compression has not been too prolonged [11]." So after hundreds of years, the mystery was finally solved. |

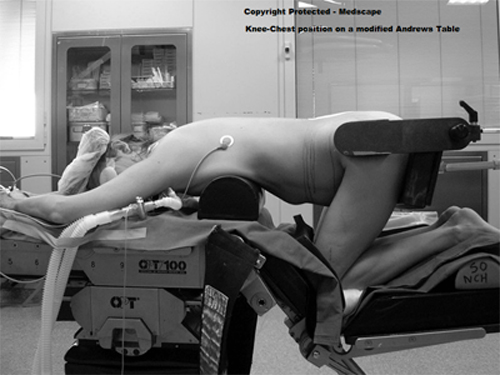

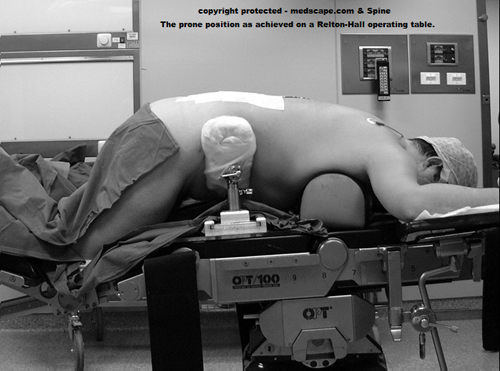

In general, there are two types of tables used to perform micro/open discectomy procedures: the Relton-Hall table (which yields a more prone patient position) and the Andrews table (which yields a knee-chest position). *Sometimes these are called frames instead of tables.

|

|

So which one is best? The research shows that both tables are about the same and afford the best possible position for surgery.

How do you know that? The research:

In 2005, Rigamoni et al. [14] published the results of their investigation into which surgical table would afford the best results following micro/open discectomy. More specifically, they wanted to see which table minimized intraoperative bleeding. In general, intraoperative bleeding is a direct result of the magnitude of intra-abdominal pressure, which can be manipulated by placing the patient in different positions during surgery.

In this study a total of 30 patients ready for single level lumbar microdiscectomy had their intra-abdominal pressure measured through a urinary bladder catheter together with airway pressure. Several different positions were tested in the patients, who were randomly assign these positions. the bottom line of the investigation was that there was no statistical difference with regard to the more prone position of the Relton-Hall table, versus the more knee-chest position of the Andrews-type table [14].

There are also other frames commonly used, such as the Jackson frame.

PICKING VS. SEQUESTRECTOMY: To pick, or not to pick--that is the question.

One of the major complications with microdiscectomy or open discectomy is recurrent disc herniations (i.e., the herniation was surgically removed, but it returned again--through the same annular tear). More specifically, the incidence of such reherniations is, depending on the source, between 1 and 11% [23-25].

In order to reduce those percentages, surgeons perform either type of discectomy via two methodologies: to only remove the herniated material that is outside of the confines of the annulus fibrosis (this type of surgery is called a sequestrectomy); or to explore the annular tear (inside the disc) and remove any fragments of nuclear material (I call this camp "the picking technique") that may be lurking about. The latter methodology is the norm.

You see, many surgeons believe that aggressive removal of nuclear fragments within the annulus will prevent further reherniation simply because there will be less nuclear material to herniate.

However, there is scientific research that contradicts this general belief. An especially scientifically strong randomized controlled trial [25] of 84 patients demonstrated that sequestrectomy resulted in fewer reherniation at the one year time point [25]. However, those same researchers found no difference between the two techniques in subsequent investigations at a two-year follow-up [22, 23].

Bottom line: the research says when it comes to open versus microdiscectomy there is really no difference between sequestrectomy and traditional "picking technique."

As a side note, there is a third school of thought that not only performs a sequestrectomy and "picking" of the annular tear, but also uses a special dye to stain the walls of the annular tear for pre-fragment / degenerated tissue, which in turn is removed. There is virtually no research on this form of treatment, so the jury is still out on whether or not it is efficacious.

THE FUTURE? Endoscopic Microdiscectomy:

|

In hopes of mitigating tissue damage via dissection, surgeons are now using endoscopes to perform and even more minimally invasive form of microdiscectomy. Although the so-called microendoscopic discectomy is a relatively new procedure, it allows for smaller incisions, less tissue trauma, no need for general anesthesia, reduced hospital stays, and reduced cost when compared to open microdiscectomy [15]. |

It was Foley and Smith whom more recently reported on the latest innovation of endoscopic discectomy. [31, 32]. This approach is a hybrid between a percutaneous flavor of discectomy and open microdiscectomy. They named this procedure microendoscopic discectomy (MED). More specifically, this procedure uses a K-wire to get down to the lamina on the side of the herniation. Once in its proper position, A series of dilators (METRx-MED system)--the first is very small and the others are added in increasing Order of diameter--are placed over the K-wire, which have the effect to push the paraspinal musculature off the lamina. The working channel of the endoscope is placed over the final dilator and finally the endoscope is attached. Then a standard microdiscectomy is performed which includes a hemi-laminotomy and sometime a medial facetectomy, followed by a removal of part of ligamentum flavum, then retraction of the thecal sac and nerve root--this exposes the disc herniation, which is then removed. If the surgeon so desires, he can attach a standard microscope to the system instead of an endoscope.

One touted strength of this METRx-MED system over minimally invasive endoscopic techniques for disc herniation removal is that it has the capability of addressing bony stenotic conditions, sequestrations, as well as small contained disc herniations. Observational studies have demonstrated the procedures short term efficacy [32] and long-term efficacy [33].

While the jury is still out on the efficacy of endoscopic microdiscectomy, there is some evidence hinting at their superiority to open discectomy and even microdiscectomy. More specifically, in 2002 German investigators Schick et al. published the results of their study that pitted open discectomy against endoscopic discectomy. They were specifically interested in whether or not use of the endoscope mitigated stress/injury to the dura and nerve roots when they are retracted out of the way during discectomy. To accomplish this, they monitored the lumbosacral nerve roots electromyographically during the operations of 15 patients who underwent open discectomy and 15 patients who underwent endoscopic discectomy. The results indicated that the endoscopic technique afforded less nerve root irritation (as confirmed by EMG) when compared to the open procedure [88].

We shall keep an eye on this technique and report any further studies showing its superiority.

REFERENCES:

1) Atlas SJ, Keller RB, et al. “long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10 year results from the main lumbar spine study." Spine 2005; 8:927-935.

2) Leonardi M, Boos N. “Disc Herniation and Radiculopathy." In: Boos N, Aebi M, Spinal Disorders: The Fundamentals of Diagnosis and Treatment. Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2008.

3) Spengler DM. “Lumbar discectomy. Results with limited disc excision and selective foraminotomy." Spine 1982; 7:604-7.

4) Henriksen L, Schmidt K, Eskesen V, Jantzen E (1996) a controlled study of microsurgical versus standard lumbar discectomy. Br J Neurosurg 10:289-293.

5) Williams RW (1978). "Micro-lumbar discectomy: a conservative surgical approach to the Virgin herniated lumbar disc." Spine 1978; 3:175-182.

6) Ross JS, Robertson JT, et al. “Association between peridural scar and recurrent radicular pain after lumbar discectomy: magnetic resonance evaluation.” Neurosurgery 1996; 38:855-863.

7) Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. “the failed back surgical syndrome. Reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments." Spine 1996; 21:626-63.

8) Katayama Y, Matsuyama Y, et al. “Comparison of Surgical Outcomes between Macrodiscectomy and Microdiscectomy For Lumbar Disc Herniation: a Prospective Randomized Study With Surgery Performed by the Same Spine Surgeon." J Spinal Discord Tech (2006) 5:344-347.

9) Tullberg T, Isacson J, Weidenhielm L. “Does Microscopic Removal of Lumbar Disc Herniation Lead to Better Results Than the Standard Procedure? Results of one-year randomized study." Spine 1993; 1:24-27.

10) Breasted JH (1930) Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, in Facsimile and Hieroglyphic Transliteration and with Translation and Commentary, 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Oriental Publications.

11) Mixter WJ, Barr JS (1934) Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med 211:210-225.

12] Wetzel FT, Hanley Jr. EN. “Spine Surgery: A Practical Atlas. The McGraw-Hill Companies 2002; New York.

13) Henrik Weber, '1982 Volvo Award in Clinical Science' "Lumbar Disc Herniation: A controlled, Prospective Study with Ten Years of Observation." Spine - 1983; 8(2):131-140

14) Rigamoni A, Gemma M, et al. “prone versus knee-chest position for microdiscectomy: a prospective randomized study of intra-abdominal pressure and intraoperative bleeding." Spine 2005; 17:1918-1923.

15) Daniel H Kim, John J Regan. "Endoscopic Spine Surgery and Instrumentation."; Thieme medical publishers: New York 2005

16) Deyo RA (2007). “Back surgery-who needs it?" N Engl J Med; 356:2239-2243.

17) McCulloch JA (1996) focus That issue on lumbar disc herniations: macro-and microdiscectomy. Spine 21:45S-56S.

18) Gibson JN, Waddell G (2007) surgical interventions for lumbar disc prolapse: update Cochrane review. Spine 32:1735-1747.

19) Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, et al. (2007). “Surgery versus prolonged conservative care for sciatica." N Engl J Med 356:2245-2256.

20) Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, (eds.): Operative neurosurgical techniques. 1st ed., Grune and Stratton, New York, 1982

21) Fager CA: lumbar discectomies; a contrary opinion. Clin Neurosurg 33:419;56, 1986.

22) Katayama Y, Matsuyama Y Yoshihara H, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between macrodiscectomy and microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniations: a prospective randomized study with surgical performance at the same spine surgeon. J Spinal Discord Tech 2006; 19(5): 344-347.

23) Barth M. Diepers M, et al. "Two-year outcome after microdiscectomy versus microscopic sequestrectomy. Part 2. Radiographic evaluation and correlation with clinical outcome." Spine 2008; 33(3): 273-279.

24) Yasargil MG (1977) microsurgical discectomy: a conservative surgical approach to the Virgin herniated lumbar disc. Adv Neurosurg 4:81.

25) Caspar W (1977) a new surgical procedure for lumbar disc herniation causing less tissue damage through a microsurgical approach. Adv Neurosurg 4:74-80.

26) Dandy WE (1918) Loose Cartilage from the Intervertebral Disc Stimulating Tumor of the Spinal Cord." Arch Surg 68:5-11.

27) Wera GD, Marcus RE, et al. Failure within one year following subtotal lumbar discectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90:10-15.

28) Isaacs RE. Podichetty V, Fessler RG. microendoscopic discectomy for recurrent disc herniations. Neurosurg Focus 2003; 15(3):E11

29) Thome C, Barth M, et al. Outcome after lumbar sequestrectomy compared with microdiscectomy: a prospective randomized study. Neurosurg Spine 2005; 2(3): 271-278.

30) Dandy WE. Loose cartilage from intervertebral disc simulating tumor of the spinal cord. Arch Surg 1929; 19:660-672.

31) Foley KT, Smith MM. Microendoscopic discectomy. Tech Neurosurg; 1997; 3;301-307.

32) Smith MW, Foley KT. "MED: the first hundred cases." Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Seattle, the BA, October, 1998.

33) Brayda-Bruno M, Cinnella P: Posterior Endoscopic Discectomy and other procedures. Eur Spine J 2000; 9(suppl):S24-S29.

74) Boos's book: spinal disorders: fundamentals of dx and tx.

88) Schick U, Dohnert J, et al. “microendoscopic lumbar discectomy versus open discectomy: an intraoperative EMG study." Eur Spine J 2002; 1:20-6

110) Breasted JH (1930) Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, in Facsimile and Hieroglyphic Transliteration and with Translation and Commentary, 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Oriental Publications.

111) Ohnmeiss DD, et al. "Degree of disc disruption and lower extremity pain" Spine 1997; 22(14):1600-1605

112) Ohnmeiss DD, et al. "Relation between pain location and disc pathology: a study of pain drawings and CT/discography." Clin J Pain 1999;15:210-7.

114) 14) Herkowitz HN, Dvorak K, Bell G, et al. "The Lumbar Spine-3rd edition." Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2004; Philadelphia, PA

153) McCulloch JA (1996) Focus issure on lumbar disc herniation: macro-and microdiscectomy." Spine 21:45S-56S.